Soul Blader / Soul Blazer (1992, Quintet)

Following the release of Ys III: Wanderers from Ys in 1989, Nihon Falcom suffered an exodus of several key staff members due to quibbles with management leading to the forming of several splinter companies. Quintet was formed by the writer and director of the first three Ys titles, Tomoyoshi Miyazaki and Masaya Hashimoto respectively, who debuted in 1990 on the Super Famicom their first game, ActRaiser, a sidescrolling action game whose stages are framed by simple city simulation segments. The player takes the role of God, alternating the direction of the building of several cities from above to personally battling monsters preventing the development of the aforementioned cities down below. Along for the ride was now-ultra famous videogame music composer Yuzo Koshiro to provide the soundtrack, altogether culminating in a unique and compelling experience that narratively fused addictive uncomplicated city simulation with expertly designed sidescrolling action platforming and epic boss battles. The game works as well as it does because of the simplicity of the city building segments; complicate it and the action scenes would feel less significant and more random, necessitating their being spread more thinly either by elongating the scenes themselves or having more smaller ones sprinkled throughout (see the ActRaiser remake's failure). Remove it entirely and you have a mere competent action game, which are a dime a dozen. The balanced frequency of the back and forth in ActRaiser's structure deepens the overall experience in proportion to the lack of more sophisticated mechanics in each of its constituents.

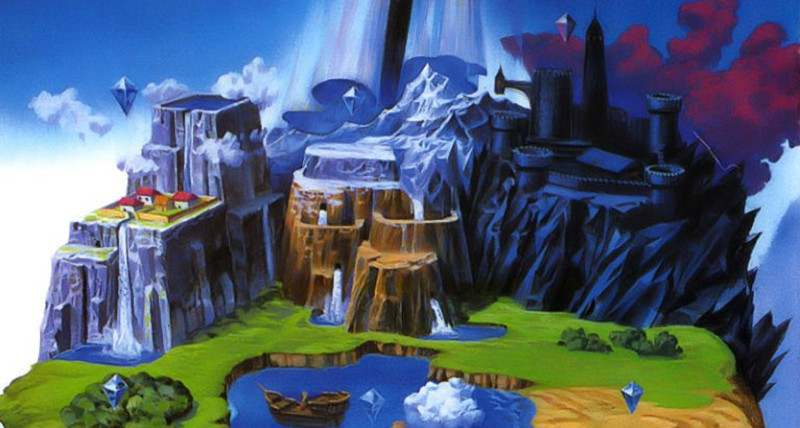

Soul Blader, released on the Super Famicom in 1992, is in story and in structure a spiritual sequel to ActRaiser. In story in that your character originates from the heavens and is commanded by God, who in the previous game you controlled directly, to restore the world and free its people from an underworld overrun by monsters, and structurally in the way that you alternate between the overworld and underworld segments and how they feed into each other. Fighting monsters in the underworld to seal the generators that they spawn from (much like the monster generators in the city segments of ActRaiser), of which there are many, will gradually change the overworld from an empty field into a thriving town. In turn, things that you do in the overworld influence your ability to progress in the underworld in several ways. Like ActRaiser, this takes place over several separate diverse areas that you select from a map, each with their own overworld, underworld, and big boss, though this time in a strictly overhead action RPG perspective in all modes. It's this staggered, lock-and-key style progression between these two phases, with puzzles that rarely vex but still feel satisfying to complete and don't get in the way of the complimentary action, that keeps Soul Blader interesting for all of its runtime. I would say that the overworld city segments aren't quite as engaging as ActRaiser's city simulation segments, being that the former are just standard JRPG towns where you talk to people and maybe solve a puzzle or two, though the link between over and underworld feels a bit stronger than ActRaiser's in that they affect each other in more direct and obvious ways.

The underworld segments consist of labyrinths filled with "monster lairs", little circles that generate a finite number of a particular type of monster, which once you've destroyed all of the enemies that spawned from it will turn into a button that you can press. Once you press the button, one of several things can happen. Maybe a new path will open in front of you, or maybe the scene will change to that of the overworld where you see a new animal, person, or even entire building appear out of thin air before returning you to the action. The compulsion to keep destroying monster lairs and pressing buttons to see how many things you can unlock before needing to return to the overworld drives the progression in a hypnotic fashion. The combat is simple: you can swipe your sword with the B button and do big damage to the enemy or use the L or R button to "crab walk" (strafe) with your sword held out in front of you to tickle them and gradually drain their health. The hero cannot move diagonally, nor can most enemies; in addition, enemy AI is usually very simplistic and there isn't much randomness, if at all, to their movements, which taken together can lead to fun tactical setups wherein your character hides next to a block or nestles in a corner in a certain way to dispatch enemy after enemy free from harm as they beat an identical path to you from a nearby generator. Positioning is often key to success. The thematic diversity of each area you visit is reflected in enemies as well, for as far as I can tell no two areas share a single enemy type, and each enemy type is unique in method of attack as well as in visual design. The basic combat overall isn't much more complex than the first Zelda, but achieves success through sheer variety of combatants and by its directional limitations.

The bosses of each area are quite large and imposing and have some pretty tough to crack patterns; I was often at a loss as to how to even begin to take them down. However on such a boss I would try and try again until I could figure out a pattern of my own, and all of a sudden, when the previous attempt had drained me of two full health bars, something would click and I could then completely own the boss without having to heal at all. There's a very thin line between certain death and figuring out the right pattern to these bosses, and when you do figure it out it's like you've broken it, like you weren't really supposed to do it this way. It's a great feeling. It really brings out the "action" in "action RPG": it's not your character's level or even the items he's gathered that bring victory, it's your actions and your capabilities. The bosses are almost always invulnerable to magic; you learn several spells throughout your journey but you don't really use them much anywhere, or at least it's almost never necessary to use them. Some spells I didn't touch at all. They come out of this orb that constantly spins around you and are often hard to aim because of it, so I rarely bothered.

Soul Blader's character art is quite reminiscent of Ys 1&2 on the PCE in its basic and cartoony style, but it gets the job done. The background art is consistently incredible, with the sea area wherein you walk underwater being a highlight, as well as the final area which I won't spoil. Also for a mechanically somewhat spartan early Super Famicom title it has a good sense of humor, I found myself chuckling at the dialogue quite a bit. The music takes its soundfont from ActRaiser, but Yuzo Koshiro was off doing stuff for Sega I guess, so this time the music is handled by Yukihide Takekawa, and he does an admirable job. The mood leans more toward funky and aloof in contrast to Koshiro's dramatic and direct; more befitting a down-to-earth adventure. It's also absolutely dripping with some seriously SNES-ass slap bass, and I love it.

So aside from some superfluous magic spells, Soul Blader's leveling and item distribution runs right up against the requirements for progression; leveling up in particular feels almost out of sheer obligation to being an RPG in that grinding isn't ever necessary or even really possible as once you've cleared a monster lair it doesn't come back, and there's never a reason to repeatedly clear out the remaining very few monsters that do respawn. Furthermore, in a journey that's mostly strictly linear and meted out in discrete standalone areas, each of which you cannot progress past before doing almost everything in them, you're never out of your depth facing monsters stronger than you're ready to handle. In a sense you could say that clearing every monster lair is a kind of grinding as you don't have to take down every single one of them in every underworld screen to progress to the next area, but there's no obvious way to tell which ones are significant and which aren't so you'll probably end up doing it anyway. With the low time investment afforded by the action of Soul Blader's genre's namesake there's nothing chore-like about it; it never feels like grinding. Item and equipment collection takes a similar trajectory, though with a wider berth; there are several quite useful things you can miss entirely and still complete the game. There's a similar kind of perfunctoriness to the key item distribution as well as the leveling in that they frequently appear not too far from where you first hear about them. Often a character I just rescued from the underworld would tell me to be on the lookout for a new sword or piece of armor, after which I walked the SNES overhead action game equivalent of ten feet to find exactly that item. It always made me laugh out loud. And that's a good thing! It's charming! This minimalist approach to progression calls to mind one of the developers' previous games Ys, in which you have a full inventory and near-max level before the end of the game, here taken just a step further. Streamlining "the JRPG progression" in this manner works well in Soul Blader, structured as it is. After hours of the game never seeming to want to bother the player with having to search too hard for items, though, the other shoe drops and you'll need to do some backtracking over previous areas. Too many players and critics bemoan the idea unilaterally, that you should never have to see things you previously saw in the same playthrough, but I say rubbish to that. There's bad backtracking, in which you repeatedly comb over the same small area that you just visited, but there's also good backtracking in which you take a sweeping bird's eye view of everything you've seen and done over a long journey. If an environment was fun to spend time in once, then why wouldn't you want to again after the fresh impression it made on you has long since faded? The narrative progression may be obvious in the timing of the backtracking requirement, but it's also neat and tidy. By the end of the game you feel like you've done just about everything there is to do in the world, evoked not by resignation but by a worthy accomplishment.

Soul Blader is in more than sufficiently complimentary proportion wide and deep. The width of its stratified world and structure is filled with just the right amount of mechanical depth to feel neither overdesigned nor stretched thin. Most items in the game are required and have some specific purpose as in Ys or The Legend of Zelda, but the addition of a few optional but useful ones do a lot to deepen the world, in that everything isn't just there to help you on your journey, they're incidental artifacts of the world you're saving. The game's narrative progression grips tightly around its mechanics and wastes little. It presents the player a captivating world of a particular size, scope, and structure, and nearly perfectly fits in a matching set of rules with which to navigate it. And that's good game design.

Final rating: 5/5 (Great)