Tatsujin / Truxton (1988, Toaplan)

A few years ago after I got my first shmup 1CCs in Batsugun Special and then DoDonPachi, and after having spent a good amount of time with many other games of the danmaku persuasion, I had the desire, for whatever reason, to take a history lesson and play the earliest shmup I could find that still had a decent resemblance to the more modern Cave games I had become accustomed to. Nowadays I would probably place that designation more squarely with Hishouzame for reasons I may go over in a future review, but at the time I decided on its predecessor Tiger-Heli. It was, after all, Toaplan's first shmup, and I knew that Cave could be considered an offshoot of Toaplan and were thusly influenced. Audiovisually it isn't much, considering it came out in 1985 and all, and if it weren't for the historical interest I likely wouldn't have given it a shot in the first place. In terms of mechanics it's a hard sell too; your helicopter is super slow, your shots don't even reach half the length of the screen, and the powerup and bomb mechanics are strange and clumsy compared to the more refined ones found even in its direct successors. But one thing really struck me during those first few credits: I had to play it completely differently than a Cave game. Flailing around trying to weave through enemy fire meant death 99% of the time. Luck was not a factor. Quite simply, the heli's slow speed, massive hitbox and delayed bombs meant I had to know cold what was coming up next and plan accordingly; the reflexes and chance dodges that got me scrubby 1-ALLs in DoDonPachi and Batsugun were a much, much smaller part of the equation in Tiger-Heli, where strategy and memorization were required at all times. And Hell, I loved it. I saw it through to the clear, and though it's a short game and isn't especially difficult, its mechanics and enemy patterns lending themselves to the forming of strategies and their oh-so-satisfying execution gave me a new perspective on how shmups were designed before small hitboxes and bullet clouds became the norm. I wanted more. I felt the natural thing to do was to continue with Toaplan's fairly beefy STG catalog, and I wanted to stay on the earlier end of their history, but I didn't particularly want to spend a lot of time with another shmup with a military theme, a prevalent one in their output leading to the affectionately titled subcategory of "Toaplane" games. The weird ass powerup system of Slap Fight was not interesting to me in the slightest, so I settled on what would later become my favorite STG ever, the space alien themed Tatsujin.

Its name, which can be translated as "Expert" or "Master", arose from the idea that clearing it would give you, appropriately, the feeling of expertise or of mastery. The impetus behind its design, as Masahiro Yuge relates, was to create a game that the more you memorized, the better you got. Indeed, the execution barrier is quite low; though there are a lot of intimidating bullet and enemy patterns, they are just merely that: intimidating. Very rarely in Tatsujin do you need to actually dodge anything for an extended period of time, which is quite unlike its predecessor Kyukyoku Tiger. What's the difference between them? Part of it comes down to the bomb. Here, for the first time, we see the instant release bomb, i.e. a bomb that comes out and does massive damage the instant you press the button. In previous Toaplan titles (and later ones) there would be a significant delay between pressing the button and seeing the effects of the bomb, meaning their use as a panic button was very limited, but here it comes right out. The purpose of the bombs isn't only to get you out of trouble however, because unlike how Cave would later treat bomb usage in its games as something to be penalized, the game actually expects you to use them. Throughout the game you'll encounter all sorts of enemies whose attacks are simply impractical to dodge without help from this additional weapon, not to mention the game gives you bomb items quite regularly and allows you to have up to 10 in stock. There's even a section right in the middle of the game that continuously gives you bomb items so you can let 'em rip with wild abandon and still come out of it with a full stock. There is also absolutely no penalty for using them. Simply put, there is no reason to hoard bombs for long in Tatsujin; it's a weapon just as much as your main shot is. Also unlike Kyukyoku Tiger the game is strictly patterned; very little is influenced by the player, and outside of very specific occasions determining what weapon items will drop, there is no randomness in the game. Enemies will always spawn from the same origin unlike K. Tiger's irritating heli zako. The items don't even move; aside from the relatively rare 1up items they just stay put where you spawned them. Everything in the game is very much in the player's hands, and is generally very fair for it. The game gets flak from some players for having enemies that spawn from the bottom of the screen, but it's a fairly rare occurrence, and again, the game always deals the same enemies in the same exact way, so just make a note of it and avoid it next time. The strict emphasis on remembering what enemies show up and when, while not allowing for much in the way of improvisation, all for the purpose of mere survival, is what it means for a game to be a "memorizer."

I want to say, in an admittedly vague manner of speaking, that the game flows magnificently. I mean this in a couple of ways. Firstly, the game doesn't stop until the end. Well duh, but what I mean is that it literally doesn't stop scrolling, and there is no point in the game where the background loops while you fight a boss. There's no bonus tally screen at the end of each stage. You start the game with your ship emerging from the base to triumphant music, and it takes off and just doesn't stop until the showdown with the final boss. While the bosses get their own theme, they are just a part of the stage like any other enemy and can be timed out, and usually are accompanied by other regular enemies. The only time you get to catch your breath are whatever breaks there are in the enemy patterns, and by that the progression feels extremely natural. The game also flows beautifully in the way that the powerup, weapons, and speed levels are handled. The weapon system, in particular, is implemented such that you will want one particular weapon type -- of the red spread shot, green straight shot, or the relatively weak but zako obliterating blue laser -- for a variety of different situations in the game. None of them are penalty weapons, unlike many other STGs that offer a weapon selection. Powering up is handled by collecting a number of P items to get to the next of 3 possible levels; it's a very rewarding system in the sense that you have to survive and not lose a life for an extended period of time to get to maximum power, and in the sense that maximum power is very good, especially in the case of the blue laser weapon, which makes mincemeat of smaller enemies and is quite a sight to behold. The speed up items offer a couple of great incentives to get to maximum speed as soon as possible: for one, the game is designed around being fast, that is, misdirecting enemy fire and then zooming out of the way, or rushing around to kill enemies before they become too numerous. Being slow in Tatsujin often means death. But also every speed up item collected in excess gives you 5,000 points, which leads to lots of extra lives. So essentially what I'm saying is that your reward for no-missing up to around stage 3 is that you get to zoom around at light speed lasering and bombing everything while racking up points and therefore extends, all because you remembered everything up to that point, and it feels pretty fuckin' great.

But then you forget about that one little enemy that spawns from the bottom right side while you're doing all this zipping around and you ram into it. All of a sudden your power, speed, and the 10 bombs you had are now gone, and you're sent back to the last checkpoint you cleared. Bummer. But really it's the same story with the majority of other shmups from around this time period; checkpoint recovery was just how these games worked back then, and here Tatsujin shines among them in this respect as well. No checkpoint in this game is unrecoverable, and the majority of them are moderately difficult but perfectly reasonable, with the toughest ones understandably residing primarily in the last stage. They're good fun on their own to figure out, each one almost like a little puzzle, and once you're familiar with most of them dying isn't that big of a deal in Tatsujin. The reason for this is because on top of the plentiful bombs you receive throughout the game, you also get lots of extra lives, both in the form of score extends and the occasional item. On one particularly clumsy run I had lost all but one life by the beginning of stage 4, and I was able to build them back up and go on to clear 2 loops! A run is rarely truly dead. I think a great balance is struck here: Give the player lots and lots of resources, but make it so they have to work to recover from a death, or in other words play a particular section in a significantly different way from how it would be approached at full power and speed. A game with checkpoints as refined as these combined with its endless loops means that to go for the standard "soft counterstop" of 10,000,000 points means that not only does the player need to learn no miss routes, but also how to recover from nearly every checkpoint without dying too much; on the other hand, for a basic 1 loop clear this isn't strictly necessary. In a certain way we could compare this to the sophisticated scoring systems of more modern shmups, wherein over time you learn and refine your pure survival route into one that follows its chaining or medaling system so as to get much higher scores.

The difficulty curve starting from the beginning aiming for a 1-ALL is basically perfect. Most likely a player will have some tough recoveries and some checkpoints that are undoable outright, making their 1-ALL rely on not dying there, which for a 30 minute play is perfectly reasonable. Still being a relative noob to shmups at the time I was going for it, it took me about 60 hours of play to achieve a clear, only credit feeding to practice. Once that first loop is cleared the game floors the rank and enemies start firing constantly at the earliest opportunity; stages 2-1 and 2-2 are close to as hard as the game gets. This is really the only thing I could call a flaw in this game: 2-3, 2-4 and 2-5 aren't much harder than their first loop counterparts, and the strategies largely remain identical. Furthermore, when you reach loop 2 the enemies' attack frequency is as high as it's ever going to get, meaning stages 3, 4 and 5 are pretty much the same no matter how many times you've cleared. Bullet speed does increase each loop up to 32, far beyond the 10 million mark that occurs around loop 7, however because the increase is so very gradual and so few players choose to play past 10 million points it's easy for it to happen totally unnoticed; for a long time most western players figured the game capped out at loop 3 or 4. The bullet speed could've really used bigger, more obvious jumps between loops. By no means does this make the game easy, but by the time you can reliably clear 2 or 3 loops you're pretty much set to get 10 million, because by then the only real obstacle is endurance. There are even reports of machines in Japan commonly being set to the highest difficulty and with score extends off entirely; while this increases the challenge greatly and would be fairly entertaining to experts of the game, it's not very welcoming to new players. Coming in cold the game isn't exactly simple even on defaults, but a common theme in retrospective interviews with Japanese arcade game developers is that they vastly underestimated the best players early on in terms of how quickly they would 1CC the games and then proceed to loop them for hours on end. This would lead to games like Same! Same! Same!, Gradius III and Tatsujin Ou, that continued the trend of looping infinitely while also being way, way harder than the games that came before from the instant you credited up, effectively locking out newcomers. A balance would be found later, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

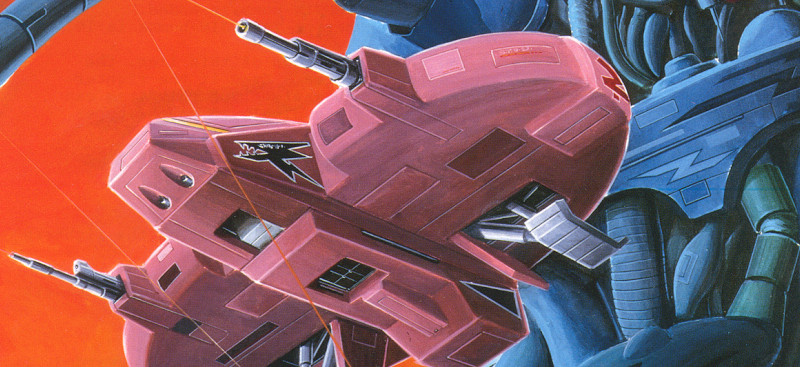

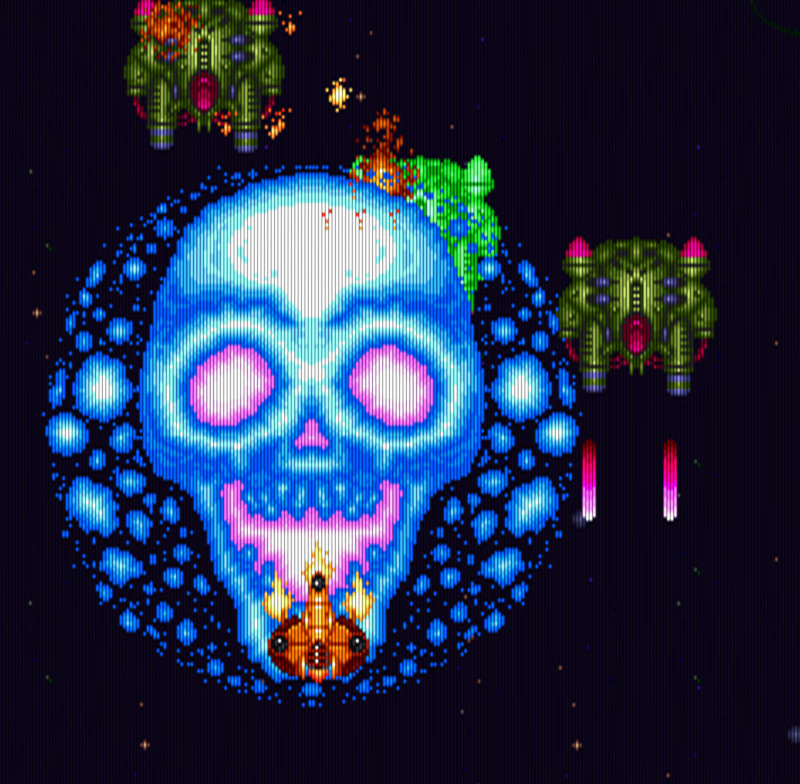

The game looks fine. The style is kind of cute and toylike, but the animation and detail pales slightly in comparison to something like R-Type, released the previous year. There's also a bit of a lack of variety in setting, as 4 of the 5 stages take place against a starry background with the occasional floating backdrop. But with the slow scroll speed and everything kind of lazily drifting in and out you feel kind of like you're floating down a river in an inner tube, but in space. What I'm trying to say is that it's a very pleasant game, aesthetically. This extends to the soundtrack as well, which shares the mostly positive attitude the sequel OST has; the game really sounds like it's rooting for you. Ultimately I will say that the game's overall theme is a bit more interesting than the military themes of the Toaplane games, and the bosses in particular are quite large and impressive. The real trademarks of the game are the aforementioned blue laser weapon which is very bright and spans the whole screen at full power, and the bomb which is a massive skull, which indisputably kicks ass.

A brief word on ports. Toaplan itself ported Tatsujin to the Mega Drive reasonably faithfully, adding a huge sidebar HUD to enforce a more vertical playfield, as would become their standard procedure when porting games to the system. The graphics are lifted straight from the arcade game, and the enemy layouts are near-identical with some wonkiness occurring here and there due to the reduced vertical space, however the checkpoints have been modified quite a bit. This becomes a real pain in stage 5, which I contend can be even harder than its arcade counterpart due to checkpoints starting in weird places that are even less conducive to recovery. Also odd is the music, which is sped up a good bit from the original, which just sounds strange. This led to some speculation that the game itself is running at the wrong speed, as if it were made to PAL specifications but released for NTSC systems, but Yuge, the game's programmer and composer has stated that they simply didn't have all the specifications for the Mega Drive's sound processor and thus weren't completely sure how to program for it before it became too close to the release deadline to fix it. Tatsujin also received a PC Engine port made by a third party. This one utilizes a full 4:3 playfield which doesn't really fit the game at all, and it increases enemy HP quite a bit, I'm guessing to compensate for the autofire that wasn't native to the arcade game; it's worth noting that the Toaplan-developed MD port did nothing of the sort while still including autofire. Overall inferiority aside, its rendition of the soundtrack is jammin'! It adds way heavier percussion to the already pretty catchy original tracks, making for an absolute improvement over the source material.

There are obviously better shmups than Tatsujin, and not everyone will jive with its leisurely pace, but absent my personal preferences I can say that the experience is substantial and varied without being overlong and includes many elements while wasting none. In the Gradius series, you don't want to get all of the speed ups lest your ship become uncontrollable. In Daioh and many Yagawa games you want to avoid picking up items in excess otherwise your rank gets too high too early. And for the love of God, do not pick up the yellow weapon in Kyukyoku Tiger. Very good cases can be made for strategic depth resulting from some of these design decisions, but the point is Tatsujin includes lots of types of items and weapons and is designed for the player to use all of them, which is a different approach from how other games either penalize the usage of some of these mechanics (intentionally or unintentionally) or streamline them into a character selection, if not out altogether. The game is also very influential, many of the second wave of programmers that came to work for Toaplan and later formed its splinter companies were Tatsujin fans. And from a personal perspective, I really enjoy a shmup that doesn't rely that much on dodging bullets but still remains difficult, which is exactly what the low execution, high memorization ethos behind Tatsujin would offer, and it is from that perspective I can wholeheartedly recommend it. Just watch your six.

Final rating: 5 out of 5 (Great)